Ma’bar-Malabar Ties: How Kayalpattinam Shaped Islam in Malabar?

Islam in Malabar, its cultural richness and heritage, is indebted to Kayalpattinam in many ways: including Ponnani Makhdooms, Mattancherry Nainas and Calicut Kunjalis. MUHAMMED NOUSHAD documents the historic overlaps between the people of Ma’bar and Malabar in Sufi lineages, scholarly exchanges and cuisine.

From Kozhikode KSRTC bus station, every evening, a green-themed inter-state transport bus of Tamil Nadu state used to set off for Kayalpattinam, until the first lockdown hit and subsequently halted it. This bus daily carried passengers from a small town situated on the western coast in Kerala to a town on the eastern coast in Tamil Nadu – an overnight journey crossing around 400 kilometres and several towns. Similarly, on the same route, with identical timing, another bus took passengers from Kayalpattinam to Kozhikode, every evening. This bus service between two ancient port towns, located by the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal, has symbolic significance, given the historic ties of their peoples in political, economic and cultural spheres, for several centuries. However, when this writer went to the ticket counter at Kozhikode, the employee informed that the service is indefinitely put off, due to the pandemic.

Malabar and Ma’bar are two regions with commendable Muslim cultural heritage, with striking commonalities of a long history: shared cultural traditions, faith practices, trade relations, scholarly exchanges, Arab ancestry and Sufi lineages. To be specific, the overlaps are varied: centuries-long trade bonds with Arabs and the arrival of Islam through traders in the early years; similar genealogies of Ba’alawi Sayyids sailing all the way from Yemen, mainly Hadhramaut; matrilineal culture; Shafi school of jurisprudence; anti-Portuguese battles; linguistic and literary exchanges; mystical Sufi tariqas and their practices. The symbiotic reciprocity of these two regions deserves to be closely examined and even celebrated by the people of two regions, as it’s hardly possible to narrate the history of one region without referring to the other.

Malayalam and Tamil descriptions at Chinna Labbaiappa Dargah

Malayalam and Tamil descriptions at Chinna Labbaiappa Dargah

The Islam of Malabar, its richness and heritage, is indebted in many ways to this faraway small town called Kayalpattinam, arguably the axis of Ma’bar. Historians may differ about the exact location of Ma’bar – a word in Arabic meaning transit – where the ships from Arabia and the West used to anchor in their prolonged voyages to places like China and South-East Asia. Most historians opine that it was the name of a region to which Kayalpattinam was the central port; some even say Kayalpattinam itself was Ma’bar, citing various sources.

However, for Malabar, undoubtedly, Kozhikode assumed the central port status for a long time, though there were interludes of its aura declining and major trade operations shifting to other ports nearby. With the risk of being historically reductionist, the Ma’bar-Malabar connects could be well-captured in the long story of Kayalpattinam-Kozhikode bonds, too. You can still see many Kayal jewellers and gem merchants in Calicut, with a Kayal Welfare Association uniting them, as it does for them in any city where Kayal expats trade and thrive.

In Kayalpattinam, when you walk the streets, you see plaques in Malayalam at every major Sufi grave, as much as they are in Tamil, indicating the sizeable number of pilgrims arriving from Kerala. You can’t miss noticing the KL registered private vehicles and cozy tourist buses, reaching and leaving the town in the morning and the evening, in spite of the pandemic. Men, women and children from various towns of Malabar spend the day in the buried proximity of the town’s revered Sufis. Ziyarat (sacred visits) to Tamil Muslim shrines by Malabari Muslims is a time-honoured practice and it has other destinations, too, as Ervadi and Nagore also lie in the same pilgrim route. But unlike them, Kayalpattinam does not have a single popular Auliya; but everywhere you get to see a saint in the town.

Reputed Tamil author Salai Basheer says, “the people of Kayalpattinam have got deep bonds with Kozhikode, Ponnani and Kochi. The links are to be preserved and kept alive. Many of our scholars and Sufis have taken pain to spread Islam and its culture in Kerala at different times. I have noticed that when pilgrims come from Kerala, they precisely go to the places where Kerala has got historic connections. I feel it is like an expression of gratitude to the debt they owe them; it is beautiful.”

Mahlarathul Qadiriyya Sabha

The death anniversary festivals of Sufis, locally known as kanthuri, are attended in commendable size by Malayali Muslims – the most noticeable crowd is at the kanthuri held at Mahlarathul Qadiriyya Sabha, commemorating the legendary Baghdadi Sufi, Shaikh Abdul Qadir Jilani, whose spiritual path Qadiriyya historically has a sweeping sway both in Ma’bar and Malabar. During the annual Bukhari Shareef event, where the entire hadith text is recited and special prayers are held, at least half a dozen buses reach from different Kerala towns, says Kayalites. When Malabaris come to Kayalpattinam, particularly in the months of Hajj and after Ramadan, they enter shrines like Mahlara and Thaika Sahib Appa’s dargah and recite hagiographies, hymns and conduct prayers. Nobody asks permission, nor does any local check on them. This eloquently interpretable act of mutual trust is an age-old tradition of two peoples who share intimate, multi-generational spiritual bonds crossing miles of distance and linguistic barriers.

Nainas, Makhdooms & Kunjalis

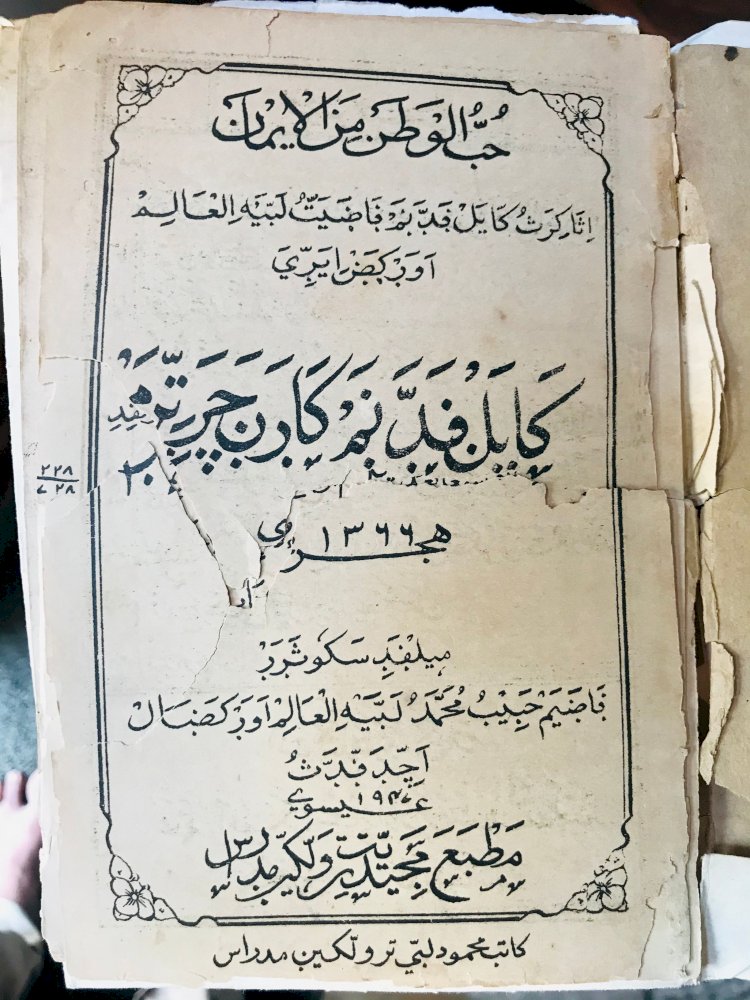

Acclaimed Malabar historian and archivist Abdurahiman Mangad says, “Islamic culture and scholarship in Malabar owe a lot to Kayalpattinam and our interactions with it in different ways. Many scholars, eminent families and clans migrated to Kerala from there. Nainas of Mattancherry, Makhdooms of Ponnani and Marakkas of Kozhikode came from Kayalpattinam and their services in the fields of trade, scholarship and anti-colonial struggle are an integral part of Malabar history. The Malabar Muslim’s linguistic heritage, Arabi-Malayalam, also takes its inspirations and influence from Arwi or Arabu-Tamil.” His archival collection has a few important Arabu-Tamil works printed in Kayalpattinam.

Frontpage of an Arabu Tamil book on Kayalpattinam

Dr. Hussain Randathani, historian and academic, adds: “When Arabi Malayalam was developed in Malabar, there was no formal script for Malayalam language as we see it today. Our ancestors started writing Malayalam by using Arabic script. Arwi or Arabi-Tamil was their inspiration for this practice. There are so many Arwi literary works, particularly religious hymns and poems that traveled to Kerala.” He has recorded that it was in Kayalpattinam that the great Mappila poet and physician Moyinkutti Vaidyar learned Tamil, a language from which he richly borrowed words and phrases.

And in return, Arabi-Malayalam’s greatest classic Muhyiddin Mala, written in the 17th century by Qadi Muhammad, the chief religious jurist of Kozhikode, gained immense popularity in Kayalpattinam, and it still does. “The tradition of reciting Muhyiddin Mala is still active in Kayalpattinam, although it is more Dravidian here, replacing certain words of Sanskrit origin with pure Tamil words. Even today, Arwi and Tamil prints of this hagiographical text praising Shaikh Jilani are in circulation in Kayal. There is also an age-old ritual of writing the entire Muhyuddin Mala by hand in Arabu-Tamil; special pens were kept for this purpose. In many ancestral houses and on special occasions, people preferred reciting from a handwritten Muhyuddin Mala to a print one,” says Muhammad Sulthan Baqavi, a local history researcher from Kayalpattinam, who currently works as a religious teacher in Kozhikode.

Muhammad Sulthan Baqavi

“Kayalpattinam was South Indian Muslim’s first international hub,” affirms veteran journalist and author Jamal Kochangadi, originally from West Kochi and currently based in Kozhikode. “Nainas were once a privileged community in Kochi, with royal patronage. The Makhdooms who are known for establishing an excellent system of religious education and exhorting Mappilas to fight the colonial powers also came from Kayal to Ponnani via Kochi. Kochangadi still has an old grave of a Makhdoom who came from Kayalpattinam. The Kunjali Marakkars also took the same trajectory, from Kayal to Kochi to Kozhikode. The Mabar and Malabar are historically connected in multiple ways. We should think of reviving the bonds in the contemporary times”.

One of the ancient mosques in Mattancherry, Kochi, is called Chembitta Palli, literally copper-roofed mosque, an excellent example of vernacular architecture, owned and run by the Niana community of Kochi. Inside the mosque, you see inscriptions in ancient Tamil, still not completely decoded. Historian Prof. Meeran Pillai states that the inscription, written in the 15th or 16th century-old Tamil, is a hadith. The forefathers of the Naina community migrated from Kayalpattinam, in the 14th century, for trade.

Mattancherry based author Mansoor Naina, in his recently released book, Naina Charithram Noottandukaliloode (History of Nainas over centuries) traces the origin of the Naina Muslims of West Kochi to Kayalpattinam. He documents the striking similarities in marriage customs, surnames and cuisine between the Nainas of Kochi and the Nainars of Kayal. On a linguistic note, for instance, when Nainar women in Kayal are called Nachi, the Naina women in Kochi are Thachi. Mansoor says that Kayal is closely linked with Kochi, Kozhikode and Kannur. “In 14th and 15th centuries, large groups of Kayal merchants moved to Kochi, as it was emerging as a trade hub and port after the decline of Muziris. Spices were the thing that attracted Kayal traders to Kochi – cardamom and pepper were the most important of them all.

The Marakkars were another indelible marker of Ma’bar in Malabar. Without the larger-than-life naval combats of the four fearless Kunjali Marakkars, the history of Malabar would have been different, in quite assumable terms. The Portuguese would have easily conquered Calicut port and Zamorins would have lost their kingdom forever. The Marakkars did not let that happen as their unflinching fights kept the colonisers at bay, quite successfully, for a considerable period. The Mappila warriors, commanded by Marakkars, paid the debt back to Ma’bar, by helping Kayalites in resisting the Portuguese who wanted total control over the pearl trade on the Coromandel Coasts. In many battles, the warships carried Mappila fighters to the Ma’bar coast. Eminent historian Dr. J Raja Mohamad, in his thickly footnoted work Maritime History of Coromandel Muslims, elaborates how the three captains of the Calicut king Zamorin, came to rescue the Coromandel Muslims and sailed to the coast, only to taste defeat at the end of the day. The elders of Kayalpattinam testify that several Malabari warriors were martyred, along with Kayalites, in the Kosmarai area.

In a coastal village near Vethala, in Ramanathapuram district, writer Salai Basheer informs, there are graves of Mappila warriors who came to support the Kayal Muslims in resisting the Portuguese. Strikingly, a Hindu temple in Madhavan Kurishi village, in Thoothukkudi district, Kunjali Marakkar is worshipped as, at the sanctum sanctorum, Kunjali Marakkar’s deity is kept spotting a beard, wearing topi and lunki according to eye-witness accounts. A surviving mark of syncretism despite the ever-increasing climate of hatred and divisions. On a lighter note, Malayalam novelist TD Ramakrishnan’s novel Sugandhi Enna Andal Devanayika, an award winning fiction set against the backdrop of the Sri Lankan ethnic conflicts, has a chapter titled ‘Kayalpattinam’, in which the tradition of building Marakkayar warships at the old port in Kayal is narrated.

The anti-colonial struggle of Malabar, against the Portuguese, however, didn’t begin and end with the Kunjalis. The contribution of the scholarly Makhdooms – who also came from Kayalpattinam – cannot be missed. Shaikh Zainuddin Makhdoom I penned an Arabic poem titled Tahrid that invoked local Muslims to resist the invasion. His grandson Shaikh Zainuddin Makhdoom II authored a historic treatise in the 16th century, titled Tuhfat al Mujahidin, chronicling the local history and exhorting Muslims to fight against the Portuguese under the leadership of King Zamorin.

Religious Education

In Malabar, the Makhdooms established a remarkable Islamic educational system popularly known as Dars, eventually giving the coastal town of Ponnani the reputation of ‘Malabar’s Mecca’, thanks to the services it rendered to the spread of Islamic knowledge. An Arabic book written by Abdul Nasar Malaibari has profiled the Mabari scholars who taught Islam in Ponnani and Kuttichira. The renowned Malabari scholar Qadi Muhammad, Muhiyuddin Mala’s author, was also taught by Lebbai teachers with the surname al-Mabari. The Lebbai clan is famous for their religious services as many of them served and still serve as mosque imams, muezzins and religious teachers in Kerala, particularly in Kochi and the southern part.

Besides, young scholar Sulthan Baqavi informs, some of the popular texts inevitably included in Malabar dars curriculum were written by well-known Kayalpattinam scholars. “For instance, to learn Arabic grammar, Kerala darses and even modern Islamic seminaries typically use Meezan, Ajnasul Sugra, and Ajnasul Kubra, all penned by Muhammad Labbai al Qahiri, son of great sufi scholar Sadaqathullah al-Qahiri. This author also served as the Chief Qadi of south India during Aurangazeb’s regime. Another major work taught in Malabar dars system is a hagiographical hymn written by Sadaqathullah’s brother Swalahuddin. Razanath, a book of metaphors, written by Shaikh Abdul Qadar al-Qahiri is another important text taught by Keralite Usthads to train religious students.” The fact that both in Ma’bar and Malabar, the Shafi jurisprudence is being followed adds to the rationale of these scholarly exchanges.

Bukhari Shareef Center

Sadaqathulllah al-Qahiri, a great scholar born in Kayalpattinam and buried in Keelakarai, taught at Muchunthi Palli in Calicut for a while, and his Hajj pilgrim was via Malabar, adds Sulthan Baqavi, citing from a book written by Malabari scholar late Ahmed Koya Shaliyathi. In Kayalpattinam, Sadaqathullah al-Qahiri used to teach at Masjid Mikayeel to where several disciples from Malabar would come for his blessings and initiation to the sufi path.

The Sayyids of Malabar are well-respected in Kayalpattinam. Many Bukhari Sayyids and Jifri Sayyids were closely bonded with the piety and religiosity of Kayal. No wonder why the death of Shaikh Jifri Thangal of Kozhikode is annually commemorated in Kayal. There are Mawlids where his name is venerated. Another Malabari Sufi who enjoys a similar status in Kayal, with kanthuri being held, is Sayyid Ismail Jalal Bukhari Thangal of Padur. The only wedding hall in town is named after him: Jalaliyya Nikah Majlis.

Kosmarai dargah is another site where one can sense the Malabar-Ma’bar bond. According to the content of a hagiography recently accessed by Sulthan Baqavi, three of the seven saints buried at Kosmarai were frequenters to Kerala, particularly southern districts. “They did great service for Islam in south Kerala and some of their children were buried there, with the surname al-Qahiri,” says Sulthan. He also adds that the much respected Kayal Sufi Thaika Sahib Waliyullah married a pious lady from Thalassery, Kerala, though she didn’t give birth to a child. Thaika Sahib was the son of Omer al-Qahiri, who wrote the Sufi classic Allaf Al Alif, which is translated into Malayalam, a few years back.

Kayal’s Malabar affinity goes beyond the mainland Malabar, crossing the Arabian Sea, to Lakshadweep. At Periya Khutuba Palli office, you see Mahmood Rijvi, the construction coordinator of the central mosque expansion and renovation project, sitting between three graves. You don’t expect graves inside an office, do you? But in Kayal, graves and Sufis are everywhere, asleep or awake. One of those graves at the mosque office belongs to Syed Muhammad Aboo Salih Thangal of Androth island. His grandson Syed Jalaluddin Pookoya Thangal is buried in Beemappalli. Rijvi informs that every year, the descendants of the Thangal from Lakshadweep sail to Kayalpattinam during his death anniversary. Kayal’s relationship with Lakshadweep and its Sayyids is age-old. There are instances of several Sayyids sailing from the islands, in olden times, and even in recent years, and they were hosted in Kayal homes – an unusual custom in the town – as some of them were spiritual healers.

Kosmarai Dargah

Another commonality between Kayalpattinam and the coastal towns of Malabar is that of matrilineal practices. If matriliny is swiftly diminishing in Malabar, it more or less remains intact in Ma’bar. It is a fact that the Salafi revivalist movement and modernity are posing mild threats to the practice in Kayalpattinam; but in Malabar’s coastal towns, a range of reasons and contexts, including the ones that are active in Kayal, are jeopardizing it, almost successfully.

Finally, cuisine cannot be missed in the list of Ma’bar-Malabar common legacies. Food blogger Sumaiya Mustafah, who consistently writes on the cuisine and cultural aspects of Kayalpattinam, emphasizes that the food connection between these two regions is immense. “Many of our rice breads are nothing but Malabari pathiri by a different name. Our maavu roti is a kind of katti pathiri of Malabar. Koli appam which is made with rice flour, coconut milk and an egg sometimes exactly looks like a nice pathiri. And this has an Ethiopian equivalent called injera, but made out of teff grains. The very word aanam for curries and gravies is used only by Muslims in Tamil Nadu, especially the coastal breed. Non-Muslims are very new to this word. I believe, though it is dwindling in usage now, Muslims of Malabar call their specially treated curries aanams. Another unifier is the enormous use of coconut milk in both cuisines thanks to the abundant availability.” However, Sumaiya adds that this doesn’t mean everything is identical in majority culinary practices. She has observed a sea of differences, too.

The bus service between Kayalpattinam to Kozhikode may resume, hopefully, once the pandemic eventually takes a back seat. Alongside, the people of Ma’bar and Malabar will have a collective responsibility to reactivate the cultural and historic ties in more meaningful and organic ways.

[This is the sixth and final part of a series on Kayalpattinam, which comes under a documentation project on influential Muslim cultural centres in India. You may read the previous chapters here.]