From Horses to Pearls and Beyond; Trade Tale of Kayalpattinam

From ancient times to the present day, horses, pearls and gemstones marked the thriving economy of Kayalpattinam, though the gem market today paints a sorry shadow of its glorious past. MUHAMMED NOUSHAD narrates the trail of trade in Kayalpattinam.

When Marco Polo arrived in Kayal, in the end of 13th century, the foreign ships anchored at the port amazed the Venetian merchant. Terming it “a great and noble city,” he wrote that all ships that come from the west and Arabia, laden with horses and with other things for sale, touched this city. Another contemporary traveler Rashiduddin, arriving in Kayal, described the goods imported from Iraq, Khurasan, Rome, Syria and Farang; the horse was the most important of all items. The local products on export, as his list emphasized, were fine red silk, aromatic roots and pearls. Similar accounts were provided by other explorers like Wassaf and Barbosa, too.

Shiploads of Arabian horses routinely reached Kayal, intended for the ever-growing cavalry needs of the south Indian kings, particularly Pandyans and Ma’bar Sultans. This lucrative business brought huge profit for Arabs, for several years, as the Indians – ignorant of keeping and nourishing the strong but sensitive horses in the adapted climate – kept on importing, on an annual basis, spending a fortune. However, with the advent of home-bred species and newly learned horse rearing techniques, the Arabian horse trade – in the literal sense – slowly faded and ended, after seeing the peak in the second half of the 13th century.

Even today, Kayalpattinam’s oldest street is called Parimar; ‘Pari’ meaning horse and ‘mar’ meaning exchange or sales. Tamil historians have often highlighted that the visual depiction of horses in certain temple sculptures, for instance in Alwarthirunagari, a few kilometers away from Kayalpattinam, is a sign of Arab or Muslim presence in ancient Tamilakam. Certain Turks – spelled as Tulukkan in old Tamil – were signatories in the deeds of local kings, such as in the copper plates of St Theresa’s Church, that too, in Pahlavi and Kufi scripts. Besides, the Tamil Muslim community of Ravuthars, historically known for horse-trading and training, traces their lineage to Turkey.

Mahalara, an architectural marvel.

Mahalara, an architectural marvel.

When the horses stopped coming, the port of Kayal didn’t perish, though. The Gulf of Mannar offered the wealth of pearls, to set the local ships sailing and invite ships from afar. The precious stones were not at all a new discovery; the pearl fisheries had been active for centuries. The Tamil literary works of the Sangham period, 6 BCE to 3 BCE, show several references to the pearl trade of Korkai. And when the great Egyptian-Roman geographer Ptolemy reached Korkai, in the second century CE, as part of his legendary voyages to fix the inaccuracies of the world map, he called it “an emporium of the pearl trade”. Ibn Batuta was equally impressed during his stay in Ma’bar.

Either slaves or convict criminals were employed for pearl diving in the deep sea, as historians testify, with intense training to stay underwater avoiding shark attacks and prolonged submarine labour. And the exotic stones collected were exported all across the Indian Ocean, and to places as distant as China and Greece. With the slow decline of Korkai, as the sea receding to the east and the town moving inland, a few miles away, by the river Tamraparni, the port of Palaya Kayal emerged and thrived, replacing Korkai. In the medieval era, there used to be merchant guilds like "Ainooruvar", to facilitate smooth mercantile voyages in the Indian Ocean, many a time protecting the vessels from pirates. All the trading communities, irrespective of their caste and creed, from different ports, joined hands in these guilds.

Well, wealth brings its misfortunes, too. The rich resources of the Pearl Fishery Coast (PFC), the coastal line from Thoothukudi to Kanyakumari, brought inevitable conflicts and invasions. The coast was ruled by the Paravas and in a conflict with the Arabs in 1532, the former roped in the Portuguese to defeat the latter, and as compensation, they converted en masse to Christianity. The Portuguese had conquered the PFC from the Muslims of Kayal in 1525; however, the commercial contention mixed with communal zeal didn’t stop there. In 1553, an Ottoman fleet, guided by the Marakkars of Malabar, with the implied endorsement of the Madurai Nayaks, raided the Pearl Fishery Coast to recapture the business from the Portuguese, and found considerable success, but eventually lost it.

Portuguese aggression caused heavy damage to the Kayal trade.

Portuguese aggression caused heavy damage to the Kayal trade.

Drawing a horrible climax to the unsparing violence, the Paravas eventually burnt the entire village of Kayal and the local Muslims had to flee, to nearby towns and Ceylon, in available vessels. In the 17th century, it was with the support of a grant and rent-free land provided by Tirumalai Nayakkan, that the Muslims, under the leadership of one Mudaliyar Pillai Marakkayar returned to repopulate the town.

If the town’s decline started with the Portuguese aggression, the Dutch intensified it. Although the French concentrated in Pondicherry, they were ruthless in attacking Muslim ships in the sea. During the Danish period, the European conflicts – both the profit-mongering battles between them and their attacks against “the Moors” – relatively subsided, as Dr. J Raja Mohamad notes.

In Ma’bar region, although there were other vital ports including Keelakarai and Nagapattinam, Kayal mostly led the transoceanic trade as the ships operated to and fro Ceylon, Malacca and the Persian Gulf. The famous Marakkayar ships regularly sailed to Malabar, Gujarat and Bengal, for imports and exports. Not just the people of Kayal, but several Muslim towns of the Coromandel Coast had had painstaking and extended voyages to Ceylon, Penang, Malacca, several ports of the Indonesian archipelago; which altogether is another fascinating story worth-narrating.

To sum up, referring to Kayalpattinam as a historic trade town would be nothing less than apt, if not an understatement. In fact, the town has its very origin and growth thanks to the status of being a transoceanic trade hub it once had been.

The Gem Market Today

In Kayalpattinam, the gem trade is not a story of the past, though the glory is. Catapulting into the present times, skipping centuries of commerce, the gemstone business has been severely affected by a series of blows, over the last years. The reasons vary from the neoliberal policies of globalization to the relatively recent demonetisation, then the GST and now the Covid-19. Kayalpattinam appears to be a small town, but it has been globally present in the gem market, very active in Sri Lanka, Maldives, Singapore, Hong Kong and Japan. The pattern usually is to buy gems from Sri Lanka and then sell them in Hong Kong or Japan. Kayal gem merchants are a regular presence in reputed international gem exhibitions, informs a local gemstone seller.

Local vendors at Kayalpattinam beach.

Local vendors at Kayalpattinam beach.

And, interestingly, the global business presence can have its curious effects locally. For instance, even the pro-democracy protests in the semi-autonomous city of Hong Kong would affect the gem business of Kayalpattinam, testifies Jamal Ameer Sultan, an octogenarian Kayalite operating from Hong Kong. Nevertheless, despite the long legacy in the global gem business, every gem merchant you meet in town inevitably shows up a disappointed countenance, complaining about demonetisation and GST, and their hushed frustration indicates the depth of the damage, as it did to most of the businesses in the country. The coronavirus was, surely, the last nail on the coffin.

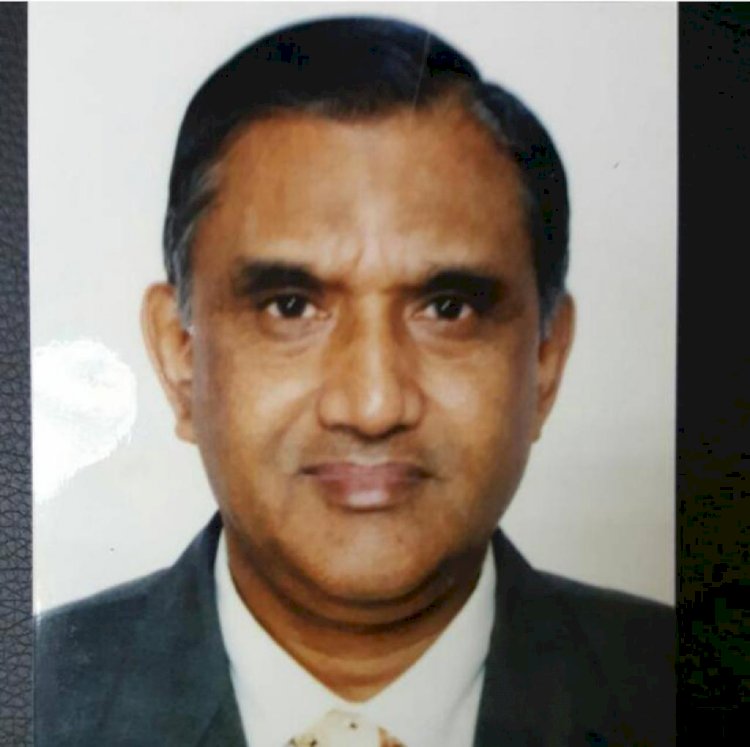

Jamal Ameer Sultan, gem businessman based in Hong Kong.

In India, Kayalites do gemstone business in almost all major cities; the main centers are Chennai, Mumbai, Kolkata, Jaipur and Delhi. Jaipur is the city where most of the business takes place and the majority of big businessmen concentrate. Salai Basheer, renowned Tamil author and a gem merchant himself, remembers there used to be Muthuchavadis or gem stations in many towns, including Chennai, Nagarcoil and Madurai, exclusively meant for Kayal gem merchants; they also served as resting place for long-distance gem traders. However, they are defunct now, except for the Muthuchavadi in Madurai.

Late TAS Muhammad Aboobaker, a retired officer from the Indian Navy and a former traditional gem merchant, told this writer that Kayalites keep selling precious stones in several towns across the Coromandel Coast and the Arabian Sea Coast, until Kasaragod, all across Kerala. He shared the experience of watching customers from Japan and the US roaming around the streets of Kayalpattinam in search of pure and original gems.

Kayal gem merchants believe their gems had a unique brand value in the market. Their stones were gem lovers’ favourite, as the town offered natural stones at reasonable rates, whereas in other famous stone markets, for instance in Japan, they sold cultured stones, veteran businessman Jamal Ameer Sultan explains. “Our business is historically linked to Sri Lanka; we have been in touch with them for many generations, for spices and pearls. We dealt with almost all precious stones in this village. Manikyam or sapphire was our specialization. We got Vaidooryam, one of the important stones of Navaratnas, either from Sri Lanka or Kerala coasts. Rubi came from Burma, Basarai from Arabia and some other stones from Thailand. We also work with semi-precious stones which we manage to get from different places in Coimbatore district,” says he. However, gemologists would say, gem classification is complex and challenging, as every principle has an exception that warrants close attention.

Jamal Ameer Sultan’s father was one of the pioneers who moved to Hong Kong to run Ameer Gems. Jamal migrated to Hong Kong in 1967, from Mumbai, and thrived, like many fellow Kayalites doing gem business across the Indian Ocean coasts – Thailand, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Indonesia, Hong Kong and more.

Salai Basheer informs that the gem business in Kayalpattinam has been reduced to a minimum now. “Another major business flourished and declined in Kayalpattinam was of leather. Since 18th century, the people of Kayalpattinam ran several tanneries in Tamil Nadu and different other parts of the country; we even imported leather. A couple of decades ago, when the Congress government imposed some regulations on the affluent, it became unaffordable for many and they stopped. Also, the more educated our people became, the less they were into entrepreneurship. The Gulf boom of the 1970s and the post-1990s globalization also made an impact on our economy. We have many expatriates now and their remittance is vital in our market,” adds he. The production of handloom lunki, mainly for the Bengal market, is another business that the town undertakes.

Men leaving Siruppalli after juma.

Men leaving Siruppalli after juma.

First Trade Show

The changing times, particularly the post-pandemic world, may necessitate different economic dynamics. Syed Haleema Thamanna, a young entrepreneur with a long line of trade under her sleeves, seems to have realized this. She is building the first mall in town, under her own firm ‘Meefa Group’. In the Kayal business circles, Thamanna is known for conducting the first trade expo in February 2021.

“Business has always been in my blood. I was a school teacher in Dubai until the first lockdown brought me home with my husband and two kids. I saw a lot of people starting new ventures, but struggling to take them ahead. Even before the pandemic hit the economy, business was not very good for many,” says Thamanna.

She also feels that the people of Kayalpattinam have a tendency to go shopping in Thoothukudi or Tirunelveli despite the availability of good products in town. “We have ample resources and sometimes people don’t know. I thought to give our traders a good platform to display their products and showcase what they were doing. The idea was to give them a sort of rebirth; and to give our people an idea of what they can avail from their town,” this was the vision behind the trade show.

Syed Haleema Thamanna, executing the first trade show.

But there was a precautionary warning: Kayalites have been running trade for centuries and none has yet attempted a trade show. ‘What if it fails?’ Thamanna thought the skeptics didn’t quite get what she imagined. With her husband Seyed Ibrahim, she set certain rules: there were both business-to-business and business-to-consumer stalls, which were kept on two separate rows. And, no two stalls will do the same business. “This was to diversify the experience and give space for all sorts of business ventures. Each applicant was asked to clearly describe their goods. We had to tell certain firms not to exhibit certain products as another firm was also doing the same business”. Eventually, at the United Sports Club’s football ground, 70 stalls were put up featuring 45 different businesses, all from Kayalpattinam, on a first-come first-serve basis.

On the first day itself, many firms realized how poorly they had underestimated the potential – having products exhausted due to huge crowds turning up, some of them had to import products from distant towns overnight. To control the crowd, in harmony with the cultural standards of the town, the organisers allowed only women after 4 pm on the final day.

A space to boost business in Kayal: when the trade show was inaugurated.

A space to boost business in Kayal: when the trade show was inaugurated.

Businesswomen are nothing new in Kayalpattinam, though. The traditional neighborhoods of the town once saw a system called Vetta where women gathered and sold commodities ranging from snacks to embroideries. Now, women have successful firms in gold, food, clothing and e-commerce. The most popular woman-owned shop probably is Riham’s Boutique, by Maryam Jameela, who runs textile shops in Chennai and Coimbatore as well. Several women in town prefer the textile business and go to places like Tirupur, Chennai, Kanchipuram and Kolkata, for buying garments in bulk quantity, depending on their customers’ needs, informs a businesswoman. Another popular female entrepreneurship is about food, including cakes and cookies; the new generation of girls has taken the business further by using Instagram.

[This is the second part of a series on Kayalpattinam, which comes under a documentation project on influential Muslim cultural centers in India. To read the first part, you may click here]